In a couple of days’ time President Ramaphosa will be making his annual state of the nation address. It is an opportunity for the head of our government to both take stock and set out his agenda for the next 12 months. One issue which should be at the top of his to do list is education.

South Africa’s education system continues to be dogged by stark inequalities and chronic underperformance with a child’s experience very much depending on where they are born, how wealthy they are, and the colour of their skin. As we know, many of the problems have deep roots in the legacy of apartheid, but they are also not being effectively tackled by the current administration. The result is that many schools are struggling with crumbling infrastructure, overcrowded classrooms and poor educational outcomes. In terms of results the top 200 schools achieve more distinctions in maths than children in the next 6,600 schools combined. More than three quarters of children aged nine cannot read for meaning – in some provinces this is as high as 91% (Limpopo) and 85% (Eastern Cape).

The education system mirrors the fact that South Africa is one of the most socio-economically unequal countries in the world. Black South African households earn on average less than 20% of white households whilst nearly half of the black population is considered to be below the poverty line compared to less than 1% of the white community. Recent austerity measures have worsened the situation for the poorest and most disadvantaged. At the same time, as we see played out on the TV every day in the Zondo Commission, corruption is a major problem impacting on both available resources and confidence in government.

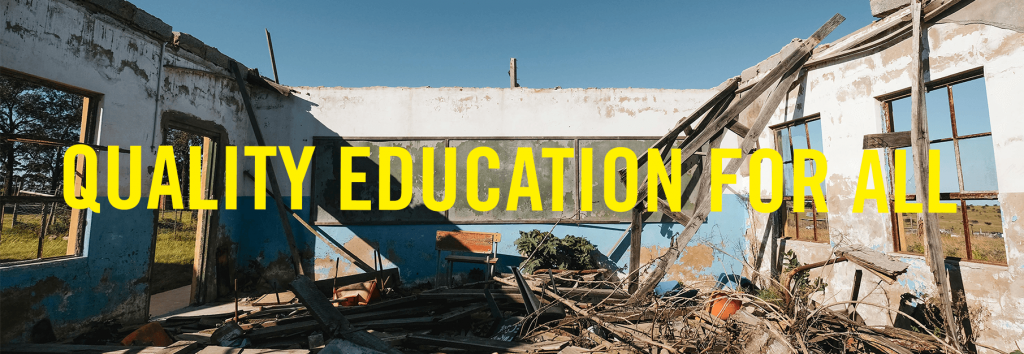

It is within this appalling context that Amnesty International South Africa is publishing today the results of a two-year research project looking into the state of education. Our research focusing on Gauteng and Eastern Cape but also drawing on a wealth of national data, found numerous examples of schools with poor infrastructure and lacking basic facilities. These included:

- badly maintained buildings that had never been renovated, many of them dating back decades to the apartheid era and even previously;

- hazardous buildings with dangerous material such as asbestos putting the safety and security of learners and teachers at risk;

- unhygienic, poorly maintained and unsafe sanitation, with some schools only having pit latrines;

- overcrowded classrooms without sufficient basic equipment and materials such as furniture and textbooks; and

- lack of security exacerbating the problems of vandalism and burglary.

All of these issues impact on the enjoyment of the right to education as well as learners’ other rights such as to water, sanitation, privacy and dignity as highlighted by their testimonies that we collected.

Many of these shortcomings are in breach of not just South Africa’s international human rights obligations but the government’s own Minimum Norms and Standards for educational facilities. In 2013, the government enacted these binding regulations requiring it to ensure that by November 2016 all schools have access to water, sanitation and electricity; all plain (unimproved and unventilated) pit latrines are replaced with safe and adequate sanitation; and schools built from inappropriate materials, such as mud and asbestos, are replaced.Yet as the government’s own statistics show it has not met these targets.

In 2018, the government’s statistics show that out of 23,471 public schools 19% only had illegal pit latrines for sanitation with another 37 schools having no sanitation facilities at all; 86% had no laboratory; 77% had no library; 72% had no internet access and 42% had no sports facilities; 239 schools lacked any electricity. To put this in context 56% of South African school principals recently reported in an international survey that a shortage of physical infrastructure is hindering their school’s capacity to provide quality instruction – this is compared to an OECD average of 26%. As many as 70% reported a shortage of library materials compared to an OECD average of 16%.

This repeated failure is not just a question of institutional accountability but has consequences for the life chances of thousands of young people who have the right to a better life regardless of their status or circumstances.

Field research reveals poverty of school facilities

Our field research was reinforced by a survey we conducted with the National Association of School Governing Bodies (NASGB) amongst 101 School Governing Body (SGB) representatives in three provinces – Gauteng, Eastern Cape and Limpopo. Some of the key findings are that only 17% of respondents indicated that either all or most school buildings in their area had been renovated in the last 20 years; 37% said that in their area at least some schools do not have enough classrooms, including 11% who said that none of the schools in their area do; 24% responded that none of the schools in their area has any sports facilities and 38% said that none of the schools has a library.

One of the key infrastructure issues is poor sanitation which impacts on a range of rights including education, water, sanitation, health, privacy and dignity. Amnesty International South Africa researchers found numerous examples with badly maintained, broken or unsanitary toilets, including pit latrines. According to our joint survey, 47% of respondents across the three provinces indicated that schools in their area had pit toilets, including 21% where either all or most schools had them. Eastern Cape scored the worst, with 63% of respondents indicating that at least some schools still had pit toilets, with 25% stating that all or most schools still had them. In Limpopo, 59% still had schools with at least some pit toilets. In Gauteng, 14% still had at least some pit toilets.

Clearly adequately fulfilling the right to education requires both sufficient resources and an effective means of allocation to meet particular needs. South Africa has historically spent relatively well on education. Yet during the last decade spending has plateaued and then fallen both as a share of public expenditure as well as a percentage of GDP. Most significantly real annual spending per learner has continued to fall year on year during the last decade as austerity driven budget cuts took their toll.

Amnesty International South Africa visited numerous schools that had insufficient resources to address even basic needs. Issues included budgets not taking constant thefts into account; budgets that are not needs-driven; insufficient additional funding from the Department of Basic Education (DBE) to compensate for the lack of school fees; insufficient allocation of funds provided by the DBE for maintenance and delayed payments due to a lack of planning by the Provincial Education Department resulting in money running out for activities later in the year.

Instead of an adequately funded system that ensures that primary education should be compulsory and available free for all in line with a core human rights obligation and that concrete and targeted steps to do the same at the secondary level, South Africa chooses to persist with a different system. Significant number of public schools which are still permitted to charge fees can raise additional revenue compared to those that cannot and tend to serve poorer communities and are therefore solely reliant on state funding which is often insufficient.

Our joint survey with the NASGB found that only 30% of respondents indicated that either all or most schools in their area have sufficient funding. This is often compounded by delays, with 31% responding that either none or few schools in their area receive funding on time impacting their ability to adequately resource the running of the institutions.

However, it is not just the amount of funding that is an issue. It is the way that funds are distributed which often fails to tackle or actually in some cases reinforces South Africa’s stark inequalities. Instead of reflecting the longstanding structural and demographic issues of poorer provinces the funding formula that is currently deployed often discriminates against them. In particular, the formula needs to take into account that it is cheaper to provide education in urban areas owing to economies of scale and population density together with a better provision of goods and services as well as the unequal starting points of historically disadvantaged and under-funded schools.

For South Africa to fulfil the right to education and comply with its both its own constitutional and international human rights obligations major change is needed. Not only does resourcing need to be increased incrementally to meet actual demand but also funding needs to be invested in a way that reduces inequalities and ensures the availability and accessibility of good quality education for all its children. The government should urgently review the current system of funding education whilst also setting a goal of ensuring that all public primary schools are ultimately free for users and all schools at secondary level also progressively move to end user fees.

South Africa needs to prioritise investment in meeting its own targets on critical infrastructure whilst also ensuring that all schools including those serving communities living in poverty can deliver a quality education for pupils. The complete removal of all pit toilets as urgently as possible and certainly by 2023 in line with the government’s own restated commitments must be a key priority. Other key issues such as scholar transport, teacher recruitment and retention, capacity and training also need to be given urgent attention.

By publishing this research now, with the government and President recommitting to tackling some of the key issues we highlight, Amnesty International South Africa seeks to contribute to the debate concerning this vital issue whilst offering constructive and concrete recommendations to ensure a better educational future for all children in South Africa.

Above all our report seeks to give a voice to those key stakeholders in the system – pupils, parents, teachers – to get a direct sense of how education is being delivered on the ground. Their words together with some striking photographic evidence present a stark picture of the state of education for many in the country.

Shenilla Mohamed is Executive Director of Amnesty International South Africa in Johannesburg and Iain Byrne is Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Researcher/Adviser at Amnesty International’s International Secretariat in London, UK.

For more information or to request an interview, please contact:

Mienke Steytler, Media and Digital Communications Officer, Amnesty International South Africa on +27 11 283 6033 or mienke.steytler@amnesty.org.za for more information or a copy of the report.