Every day I receive approximately 10-15 Google Alerts with news articles containing the words “gender-based violence” and “South Africa” in them. These articles cover specific incidents of gender-based violence (GBV) that have occurred, shortcomings by the police in their investigations, or yet another programme launched by government to end the war against women in this country with no sufficient budget allocated to implement it.

Statistics on reported cases of GBV in South Africa are disheartening. In the year 2019/20, 2,695 women were murdered in South Africa. That amounts to one woman murdered every three hours, which is almost five times the global average. The latest quarterly crime statistics spanning October to December 2020, show an increase of 181 reported rape cases compared to the same reporting period of the previous year, bringing the total number for that period to 12,218. This equates to a 1.5% increase and averages out to 136 cases of reported rape per day. Yet we know that rape and gender-based violence are significantly underreported and that these reported cases are only the tip of the iceberg of this pandemic.

Fuelling these cases are stereotypes and myths, patriarchal gender norms, toxic masculinity, and cultural and societal attitudes and beliefs. This is evidenced by the fact that one in three men in South Africa hold the belief that women should not have equal rights.

It is with this in mind that Amnesty International South Africa launched its first arm of the Interrupter Campaign, #InterruptGBV, in February this year. The campaign demands urgent collective action from society to end the scourge of GBV in South Africa and calls on everyone living in the country to pledge to speak up, stand up, and end their silence on GBV; to call out derogatory conversations, languages and jokes; and to interrupt the cycle of violence by educating younger generations and having conversations with friends, family and neighbours on appropriate behaviours and what needs to change.

But it is not only society that must change. The criminal justice system in South Africa is failing its people. My Google Alerts are a constant reminder of this.

Just look at the recent issues around the DNA analysis backlog. In March it was reported that Police Minister Bheki Cele had “by chance” found out that DNA evidence had not been processed for two months. The backlog had jumped from 117,000 in December to almost 173,000 by early March, because nothing had been done from January to February. Then there are reports of 50 cases of GBV being struck off the court roll or withdrawn between October and December 2020, in the Western Cape, due to police inefficiencies.

Despite all of this, the Department of Justice’s 2019/20 Annual Report boasts a sexual offences conviction rate of 75.2%. However, this is only of the cases that are prosecuted, not the total cases reported. A study by the Medical Research Council (MRC) in 2017 places conviction rates at 8.6%. Various factors influence the progression of a case through the criminal justice system, and in turn contribute towards the outcome thereof (often negatively) by creating enhanced barriers to accessing justice.

With some of the most robust and highly regarded pieces of legislation and policies addressing GBV in the world, where are things going so wrong in South Africa?

Simply put, the filtering process which sees cases drop out of the justice system, known as attrition, is a major problem. The country’s justice system is complex and comprises of the South African Police Service (SAPS), the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA), the judiciary (the courts), and medico-legal services (medical personnel collecting evidence and forensic labs analysing DNA). Attrition occurs at each of these stages, with the highest rate occurring at the police investigation stage, with most cases never making it to trial.

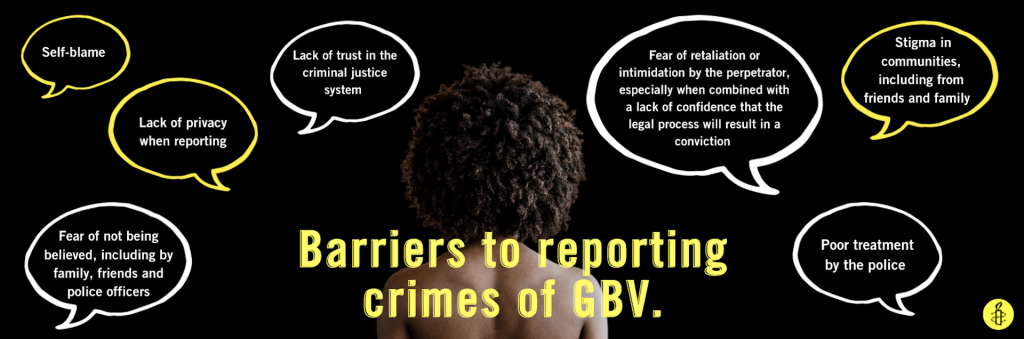

Flawed investigations result in cases with inadequate documentation and evidence to prosecute. The most basic mistakes, which should not be happening but do, such as dockets not including the complainant’s address or telephone number, or complainant statements not signed, can lead to a case not seeing the light of day. Not following basic requirements, such as taking the survivor of GBV to a private room to take their statement, offering that a female officer can assist them, and explaining their rights, leaves the victim feeling re-traumatised and vulnerable. Coupled with the attitudes and behaviours of some officers, prosecutors, medical personnel, and magistrates – fuelled by myths, stereotypes and gender norms which lead to secondary victimisation – this often results in survivors withdrawing cases, and in many instances not reporting at all. These are simplistic explanations for a complex and multi-faceted system of deeply entrenched failures.

Amnesty International South Africa recently ran an online survey, about people’s experiences navigating the justice system after they had experienced GBV. Responses to the survey support the existing research. Of respondents that did report the incident to the police (which was only 56%), 72% were not explained their rights, 64% were not taken to a private room to take their statement, 68% were not told that they could request a female officer to assist them, and 81% were not kept informed about the progress of their case. Most of them had traumatic experiences across all stages of their interactions with the justice system. The comments from respondents ranged from:

“she implied it was my fault”; “when I walked into the station I was asked ‘who was the lucky guy”; “they always give you the attitude that you deserve whatever is happening to you”; “no compassion, privacy, not treated discreetly”; “the detective handling it swore at me and told me to go hang myself”; and “I did [report], but wish I didn’t”. This is just a small sample of what is happening.

The scourge of GBV is a national issue which affects people across all divides and so collective action on several fronts is required for effective change to happen. It is not enough to only focus on changing social and cultural norms within society, just as it is not enough to only place the responsibility of addressing GBV at the feet of the justice system. It requires action from everyone and every sector. As such, Amnesty International South Africa is launching the second arm of its Interrupter Campaign, #InterruptTheJusticeSystem. Through this campaign we will be highlighting the barriers, systemic failures, opportunities, and recommended solutions to address these, focusing on direct experiences shared with us. We also call on all actors in the criminal justice system to: interrupt stereotypes, myths and norms fuelling secondary victimisation; interrupt the lack of legislative implementation; and interrupt the apathy and lack of urgency in dealing with cases of GBV.

These are some of the steps that can make a difference in combating GBV in the country. There must be consequences for perpetrators, and the impunity currently experienced within the justice system must come to an end.